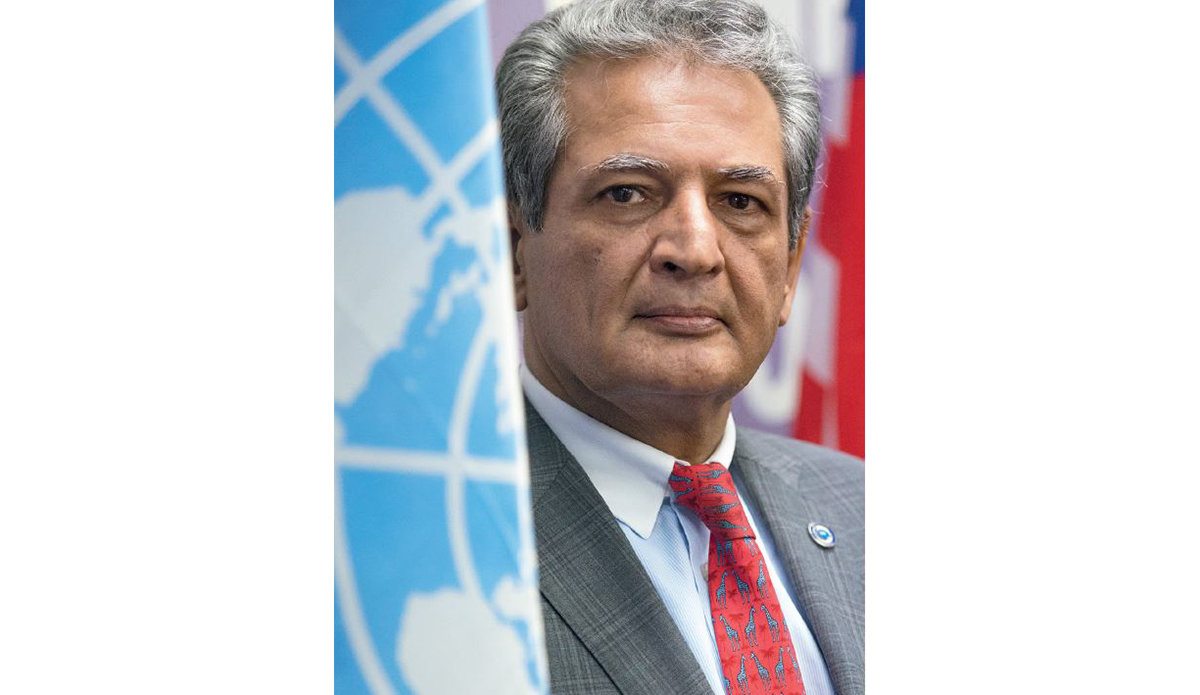

Mutual accountability must be fundamental to peacekeeping | Farid Zarif, Under-Secretary-General, Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Head of the United Nations Mission in Liberia (2015-2018)

Established in 1847 as the first independent African republic, Liberia went through two successive civil wars that claimed the lives of an estimated 250,000 people and led to a complete collapse of law and order. With international recognition of the need for peacekeeping intervention following a ceasefire agreement, the UN Mission in Liberia, or UNMIL, deployed in October 2003 with an authorized troop strength of 15,000, a police component and hundreds of civilian staff. During the Mission’s 14-plus years of operation, Liberia saw the restoration of peace and stability. The country held three, violence-free elections and has undertaken reforms to its governing and security structures, with the constant support of UNMIL.

Established in 1847 as the first independent African republic, Liberia went through two successive civil wars that claimed the lives of an estimated 250,000 people and led to a complete collapse of law and order. With international recognition of the need for peacekeeping intervention following a ceasefire agreement, the UN Mission in Liberia, or UNMIL, deployed in October 2003 with an authorized troop strength of 15,000, a police component and hundreds of civilian staff. During the Mission’s 14-plus years of operation, Liberia saw the restoration of peace and stability. The country held three, violence-free elections and has undertaken reforms to its governing and security structures, with the constant support of UNMIL.

In an October 2017 interview, Under-Secretary-General Farid Zarif, the UN Secretary- General’s fifth and last Special Representative for Liberia and Head of Mission, talked about strategies, tactics and challenges in leading UNMIL during its final phase of operation.

How did the early part of your career, working for your Government at home and in the Foreign Service, map to the challenges and issues you have faced, leading the UN Mission in Liberia?

I started early in human rights activism to help change my country. The series of changes in Afghanistan, accompanied by vast political, security and economic challenges, really put me through an accelerated process of learning in the early part of my life and career. Later on, together with a small number of other Afghan activists, we helped establish the Independent Human Rights Commission of Afghanistan, which is still functioning today, albeit recast in a different form. But at that time, it did important work in conjunction with lawyers committed to taking difficult cases to make sure due process was upheld. These activities, which continued through my early career in the foreign service of Afghanistan, were part of the country’s struggle toward a democratic and just society. Those struggles are not unlike Liberia’s struggles today.

The early part of my career shaped me as a human being, and some of those early challenges certainly map to the issues I am dealing with here in Liberia.

Later, with the UN, I did elections and political work, then humanitarian work in the field and at Headquarters and then peacekeeping in the field and at Headquarters. As an ambassador and permanent representative to the UN for seven years in the 1980s, I’d also done a lot of work inside the UN system, as well as within the governing bodies of the UN Agencies, Funds and Programmes.

A combination of years working in multilateral diplomacy, and a good mix of diverse experiences in the UN in different settings equipped me to help tackle some of the pressing challenges Liberia continues to face as UNMIL comes to a close.

Have you had a special focus here in Liberia, or a special interest or passion that derives from work in the past?

Indeed. One of them is related to my experience back home, and how a country may gradually drift toward chaos and war through neglecting the anger and frustration that builds up within society, with a government isolated from the people. That can lead to a focus on a military solution rather than addressing the causes of fragilities of a society. Unless we identify and resolve the foundational issues which drive conflicts, society will remain susceptible to breakdown and may end up falling into the entrapments of violence and war.

In Liberia, unfortunately and notwithstanding lofty visions, I see minimal evidence of serious successful advances to get the country out of that vicious cycle.

Unless we identify and resolve the foundational issues which drive conflicts, society will remain susceptible to breakdown and may end up falling into the entrapments of violence and war.

My experience in Afghanistan and in several post-conflict settings elsewhere has given me perhaps a unique focus on this challenge: how to use the UN’s resources and capabilities to help get beyond the deadlock of a heavily centralized, self-serving government that perpetuates itself, and turn it into a vehicle that delivers services to the neglected population. That can only be done if government becomes more representative, accountable and people-oriented, and that public service does exactly that: serve the public. You can’t expect that a government that is heavily concentrated in the capital would be able to deliver all the services the people need all over the country. Although decentralization/deconcentration is only one part of the needed reform, it is certainly one of the priorities where I wanted to focus my attention in support of this Government’s own agenda.

Another priority is national reconciliation. Liberia never got close to fully developing the concept of nationhood, because it always remained split across multiple divides; indigenous versus settlers, tribal versus regional marginalization, gender bias, inequitable sharing of national wealth and economic opportunities, monopoly of political space, impunity for war crimes and mass atrocities, etc. How can you overcome these divides and develop a concept of nationhood that brings everybody together around a common vision? That’s certainly been a priority for me too.

In addressing the underlying causes of the conflict and on the issue of nationhood, do you see progress?

What President Sirleaf has offered in her Agenda for Transformation and Vision 2030 addresses both these issues directly. But unfortunately, she couldn’t make significant progress, partly because of the challenges she inherited from the civil war, meaning the tension between transitional justice and peace. Regrettably, the whole idea of national reconciliation has been put on the back burner, and the Government has been unable to translate its own national agendas into the political will and tangible national capacities for managing processes of structural reform. The UN system and the donor community have not been sufficiently unified or vocal in both supporting and challenging the Government to adequately invest in addressing critical conflict drivers and deep-rooted reconciliation issues.

We should have been firmer, right from the beginning, and demanded delivery on the part of Liberians as a pre-requisite for provided support.

From the early post-war period, the UN’s emphasis on national sovereign ownership, and the systematic alignment of its projects and programmes with national priorities, arguably diluted the political will to hold the Government accountable to a higher standard of social and rights-based responsibilities. Consequently, the reforms required to strengthen social cohesion and human security, e.g. land reform, education, youth employment, local economic development, diversification of the economy, political accountability, inter-tribal relations, constitutional reform, transitional justice, have neither featured strongly nor been pursued vigorously in Liberia’s post-war recovery interventions. That is why the peace and stability are so fragile. To be fair, the calamity of Ebola and the drastic fall in prices of Liberia’s traditional export commodities dealt a severe blow to the President’s ambitious reform plans, some of which appeared to be on the right track until then.

What other priorities have driven your daily work?

I have been very much focused on prevention, particularly in the last two years when we were faced with the challenges of organizing an election that President Sirleaf described as a defining moment for the history of Liberia. This election was the first time ever in the history of Liberia that a sitting, truly representative and democratically-elected Government would be handing over the mantle of authority to another Government, elected under the same system of principles and standards. It is a gigantic leap in the consolidation of democracy and stability – a turning point, in fact. Anything that would challenge that turning point would be something that would invite my attention. I have constantly engaged with all political parties, individually and in groups. We have focused enormous effort on the agendas that mattered to them, to make sure that all the issues that could become a hindrance were discussed with solutions in mind.

These included: How do we minimize the element of suspicion between the Government and the opposition groups? How do we turn the political parties in the opposition into stakeholders for stability, peace and calm? What is their responsibility toward the public, in terms of providing a sense of vision and hope for the future? How to manage emotions and guide them in the right direction? These are questions I asked myself daily and that we thought about pragmatically as we neared the elections. We worked with the opposition as well as with the Government, the media and civil society to make sure there was a parity of sentiment and commitment, a shared understanding and a common respect for the rule of law and peaceful elections.

"We should have been firmer, right from the beginning, and demanded delivery on the part of Liberians as a pre-requisite for provided support."

This is, of course, proactive ‘good offices’ work. When I first arrived, my interest in strongly pushing on these issues frightened some representatives of the international community. Some said to me, “Be gentle.” But look at where we are with national reconciliation, which was one of the first items of the peace accord. Where is the constitutional reform? Still it is not even in draft. Where is the security transition that was spoken about? Still we have been working on the final plan. We should have been firmer, right from the beginning, and demanded delivery on the part of Liberians as a pre-requisite for provided support.

I would tell them, very honestly, that you can’t hide behind the concept of sovereignty and tell me that it’s none of my business. If it’s none of our business, why then did the international community bring 15,000 troops here to make peace in this country, spending close to US$8 billion? That makes us a natural stakeholder. We are sharing in the success, and we are concerned about potential failures. I have been telling the Government and the opposition parties that we, the United Nations, are a part of the effort to maintain the shared accomplishments here. We absolutely cannot be bystanders.

We did things for them instead of helping them do things for themselves. What brought the United Nations here? The breakdown of foundations of this country – the divisions, the marginalization; a lack of equitable opportunity created a situation for the country to collapse. And still, after years of UN work, the country is grappling with massive issues. One of them is education. The latest statistics indicate that 65 per cent of children are out of school, leaving the next generation 65 per cent illiterate. Another example is women’s rights and their participation in government.

The statistics are dismal, with 12 per cent in the House of Representatives, 12 per cent in senior Government positions, 8 per cent in the security sector. These are all things we should have helped address years ago.

But first and foremost is turning the Government’s mind-set toward people-orientation and service delivery, where those employed by the Government recognize they’re not there to support themselves but to serve the people. That’s why people across Liberia still look on the security structures as protectors of the Government alone. That mind set should have been addressed right at the beginning of UNMIL when we were helping to build capacity.

The idea now is not for me to sit in judgement. But certainly the UN could have started its work here by helping address the foundational causes of the conflict and by looking to find out why this country went to war.

What would you say are those elements that remain unaddressed?

Among them, land rights are a critical issue.

We did a comprehensive survey, asking people to identify their most important concerns. At the top of the list were land-related disputes. There’s no sense of ownership, so nobody wants to develop the land. They just live from day to day. They just collect whatever nature gives them. They do not invest themselves because they are not sure it is theirs. We must get a better sense of what belongs to whom. And based on that, we must start a land-reform process that will bring agriculture back to what could be a very productive area of the economy that would employ thousands and thousands of people.

If that happens, all these shanty towns around Monrovia will be vacated because people will have land they can call their own and start working on it. Unemployment has really reached phenomenal numbers. How long will a society be able to sustain this level of unemployment? At some point, there must be a breakdown. And that’s why I believe that fragility is very much built into the current system in Liberia. It’s systemic. Unless we change the social contract, we cannot do away with the fragility.

One of the ways of changing the status quo is to find employment opportunities, and where it is available in Liberia is in agriculture. But that won’t create jobs or income unless there is land reform. It’s a sort of domino effect. Start with adoption of the Land Rights act and pave the way for land reform so communities have access. Then people would need assistance to acquire the tools of agriculture work, access to improved seeds, and technical guidance and support. Then the country could gradually move into processing so it could reduce importation and then gradually to export. Liberia could become self-reliant. This could happen with a long-term vision. A draft of the new land rights legislation has moved forward, but despite the best effort of President Sirleaf some legislators are sleeping on it because they have vested interests. They don’t want reform.

At the international level we currently have a structural problem with the manner in which the UN and international donors deliver assistance to countries like Liberia. The UN system still does not work well as a coherent whole, and while UN coordination mechanisms may function effectively in the delivery of time-bound emergency actions, they struggle to sustain the constancy and longevity of consolidated engagement required to embed national capacities capable of assuaging the causes of conflict. This is explained by inter-agency competition for limited funds, individual “sovereign” organizational mandates, misaligned mandate timeframes and budgetary cycles and different governance structures.

Everybody must come together to envision a far more effective process for sustaining peace. The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the European Union and African Development Bank, the Government of Liberia, and all the well-wishers of Liberia – all of them should come together and coordinate to support that long-term strategic perspective, rather than competing over tiny projects here and there – a bridge here, a piece of road there. With vision, the dynamics would play out, and you would see one element supporting the other. But you must have that sense of a larger and more strategic perspective.

I don’t think that my predecessors were given the opportunity to think and operate like that, and the mandate did not give them the authority to talk about developing a strategic long-term agenda for the country. But then again, you don’t have to have a mandate to express these thoughts to the leadership of the country. That’s why I’m having bilateral meetings with the President almost every week, to a very good effect. I occasionally hear the echoes of those discussions from cabinet ministers.

So do you think that the Mission in its early days focused too much on peacekeeping at the expense of other issues?

Nothing really prevented us, in terms of mandate or resources, to engage in other areas. What we did, rightly so, was restore peace and stability, and build capacity within the institutions of the State, building up the police and helping reform many other institutions. These are major undertakings, and the UN’s role should not be diminished. We did help a lot, together with the donor community, because these institutions had virtually collapsed at the end of the civil war.

These are successes that you would attribute to UNMIL’s intervention in the early years?

These are successes of UNMIL in the beginning. Yes. Stabilization, followed by disarmament and demobilization, followed by consolidation of peace, followed by institution-building across the length and breadth of the security sector and in other areas.

Security sector reforms, work with the judiciary, and a strong focus on women’s rights issues were all very worthy contributions of UNMIL over the years. Security is now in the hands of the Liberians, and they’ve done a fantastic job of maintaining law and order. Nobody is scared. Nobody is abused. There were several armed robberies last year, which resulted in the reshuffling of police. We’re talking about a city of two million people.

But Liberia still is vulnerable and fragile. And unfortunately, if there is a trigger, violence will spread like brushfire because there is so much

accumulated anger here over the lack of prospect for change.

But Liberia still is vulnerable and fragile. And unfortunately, if there is a trigger, violence will spread like brushfire because there is so much accumulated anger here over the lack of prospect for change. The youth have no perspective of the future, and see no prospect for a better life in the future. In the absence of that, they become easy targets for extremism as pawns in the hands of politicians to be used one way or another. And that scares me.

That issue is compounded by a sense of deprivation and marginalization along ethnic lines. There is a sense that it’s only the elite few who have access to the benefits of the state. They’re the ones that benefit from the sale of iron ore, gold, timber, palm oil and rubber; they’re the ones who keep fat bank accounts and pay themselves so handsomely it competes with international salaries in Europe and the United States. They are getting so much money in their official entitlements, and on top of that they are dipping into other areas to enrich themselves. All Liberians talk about these things. So how long do we expect people to tolerate it? That’s why some think we are sitting on a powder keg, if not a ticking bomb. A trigger could ignite this place. President Sirleaf made genuine efforts to advance the anti-corruption agenda, but it is a battle that should involve everyone, from the ordinary citizen to the highest level of the judiciary.

What are some of the Mission’s achievements that haven’t made headlines but have impressed you?

Wherever I travel, I see signs, small signs that have become faded with time but still indicate that UNMIL has been there. These signs indicate that UNMIL has supported institutions across the country, in security institutions, in courthouses, in medical clinics in remote areas. We didn’t publicize it, but people who live near one of these facilities know who built it.

Each of those small, pervasive signs are indicators of where UNMIL did a lot of work in building the foundations for decentralization and real service delivery to the people who need it most, in the farthest reaches of the country. These projects helped enable the deployment of personnel from Monrovia to those remote places. Coupled with training programmes that we provided to thousands upon thousands of uniformed and civilian personnel of the Government, UNMIL essentially enabled the Government to begin operating country-wide.

Given the small amount that we had under quick-impact projects funding, this is proportionally the most manifest impact that we made, enabling institutions to find a foothold. Together with the training that we provided, the central Government managed to deploy services outside Monrovia and for the first time managed to be available to other counties to deliver traditional services of the state to remote areas. But, of course, enabling a peaceful and violence-free environment for the Liberian people is by far the most important contribution UNMIL has made.

As the Mission prepared to close, what were you concentrating on?

One good example was our regular meetings with the political parties’ leaderships, the civil society leaders and members of the media. We sat and talked about issues of concern to society, to the nation, and to us as a Mission. These served as fora for exchanging views and sharing concerns, and gave a sense of direction over time, spelling out the responsibility of all toward the people and ensuring that elections would be held in a violent-free atmosphere.

Out of the 500-plus events that we had in the context of the electoral campaign, there were only very few altercations, all insignificant: In one case, a couple of bloody noses. In Liberia, in West Africa, this is unprecedented and an accomplishment of Liberians The people should be complimented. It is a message I have delivered: Liberians should take pride in the fact that they have delivered the most peaceful, participatory, orderly and credible election in the history of this country. It’s a leap forward in consolidating democracy and good governance.

"Liberians should take pride in the fact that they have delivered the most peaceful, participatory, orderly and credible election in the history of this country. It’s a leap forward in consolidating democracy and good governance."

It is also partly the outcome of our proactive ‘good offices’ work, which we carried out together with national and regional actors, including the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), with whom we issued joint messages on key electoral occasions.

That strategy maximised the impact of collective efforts, and facilitated greater integration our common endeavours.

And it’s not just a symbolic act that we are bringing everyone together into what is now the UNMIL headquarters compound – all the UN agencies, funds and programmes, the AU and ECOWAS. We are strengthening the spirit of commonality of purpose and coordination – not just talking about it but doing it. Joint coordinated messaging and sharing the same buildings, including eventually sharing assets and services, is a process that brings us closer to strengthening that spirit of commonality of purpose and effort.

We have also engaged with the diplomatic community, the donors, and of course Liberian groups focused on specific topics in human rights, women’s empowerment, youth and so forth. These engagements are instrumental in helping us resolve contentious issues.

One recent example was the proposal to turn Liberia into a Christian state, which led to the breakup of the Inter-religious Council, and caused massive friction among different groups. Our main argument with all of those with whom we engaged was to be preventive: do not open this country to terrorists who would see this move to a Christian Liberia as creating a legitimate battlefield. In the end, the idea of the Christian state was abandoned, and Liberians sided against anything that could divide the nation further. Tolerance, accommodation, peaceful coexistence – these are the future here.

Another example was the controversy in March 2017 over the code of conduct for public officials. Some members of the Legislature took exception to the opinion of the Supreme Court regarding the eligibility of some presidential candidates, and moved to consider impeachment some of the justices, accusing them of bias. The justices responded in kind. The judges and legislators were at loggerheads; so, we stepped in together with local and regional stakeholders. We spoke to opinion-makers in the House and met with the Supreme Court and others. We finally managed to get the House to drop the original summons, and convinced the Supreme Court to nullify its own summons to the House. That constitutional crisis was averted. We never sought publicity from these interventions. They were quiet achievements. But we’ve been working hard, behind the scenes, in many ways like this, to help this country move forward and face its challenges successfully.

These seem examples of preventive diplomacy? What other work have you done along those lines?

It’s exactly that: preventive diplomacy. It is what the UN should be doing as part of all peacekeeping operations in addition to what it is tasked to do in special political missions.

Another good example is what happened on the day of elections. One of the opposition parties issued a press release, essentially a statement of complaint, and I picked up the phone and spoke with the party leader and urged him to call on his followers to remain calm, while he referred his complaint to the National Elections Commission. What I didn’t know at that point was that they had already decided they would be marching on the Elections Commission to protest. But I learned later that, after having spoken with us, they had second thoughts about doing so. All those who had grievances resorted to due process, instead of going to the streets.

We have done a lot here in terms of prevention, in the current drawdown phase and across the history of this Mission. I’m pleased about the decision of the President recently to do away with a clause in the law that described certain kinds of opinions expressed in the media as sedition, a criminal act. This clause, which was never enforced, ran counter to the freedom of press, and its mere presence in the law forced people expressing certain opinions to go into hiding or into exile in other countries. The provision was deleted from the law.

What other challenges remain in Liberia as you work to bring UNMIL to a close?

There are many challenges, including the inability of the Government to make good on some of its own promises regarding restorative aspects of national reconciliation and on women’s participation in at all levels of Government. There are challenges in doing away with harmful traditional practices, including female genital mutilation (FGM).* But not enough is being done to criminalize them.

Overall, there are huge challenges in the justice sector’s performance. As just one example, pre-trial detainees make up almost 70 per cent of all detainees, and that’s already an injustice, because some of those detainees are spending more time behind bars than they would if they were convicted of their alleged crimes. Recently, we’ve approved projects to increase the capacity of the judiciary to adjudicate cases of pre-trial detention to help reduce the backlog so they can focus on severe cases, not just traffic violations or fist fights.

Have you seen any marked improvements in these areas in the time you’ve led UNMIL?

We’ve initiated programmes by helping the construction of courts, by training judges, by building the capacity of prosecutors so they can make better cases, by helping police investigating a crime to develop a solid case that would stand in court, and we’ve worked to synchronize the relationship between these elements to deliver quality justice. But these things are coming late in the day. These projects should have started right at the beginning, with the judiciary having adequate resources to do better.

The fight against corruption is another area that should have been addressed long ago. Corruption is endemic and runs across the length and breadth of the system, with almost total impunity.

The number of rapes is also very high in Liberia. Out of all serious crimes, collectively, including murder and armed robbery and smuggling and others, one-third are rape cases. This is way too high. Even though we supported a special court on rape, the performance is horrible because they don’t have the basic tools of collecting evidence. Proving a case of murder is of course easier than proving a case of rape.

It’s a revolving door. Rapists go free after two rounds of sitting in the court because the case is dropped when there isn’t evidence to move it forward or because of the influence of the local chiefs who take bribes and bribe the courts or force a family to relocate and not show up on trial day to push the case. There are lots of evils in this society that really could have been tackled head on, but we didn’t prioritize them early enough.

Does this cause a certain level of personal frustration for you, recognizing that this Mission will shut down with unfinished business?

Yes. Exactly. None of these things should have been our preserve alone, but we should have been an instrument for commencing a process of change by demanding action by the national authorities, demanding their terms of reference in return for all the support that the international community is giving. Unfortunately, the rest of the well-wishers of Liberia, because of their own bilateral interests, did not want to exert too much pressure on the Government, and as a result, the Government has gotten away with a lack of performance, plus it has tolerated corruption, nepotism, incompetence and mediocrity.

For me, this is my last job. I don’t have a hidden agenda. It is because of the personal care I have for Liberians on the one hand and the duty of care as part of my mandate on the other hand that I must take these issues seriously.

In the end, the President has done many positive things in Liberia. Unfortunately, Ebola really brought her agenda to a grinding halt and seriously affected the good performance of the economy. The economy is now contracting, in part because of the steep fall in commodity prices globally and in part because of Ebola. Because Liberia is heavily dependent on extractive minerals and other export items, the country is suffering. Had they diversified the economy a little bit earlier, Ebola and other factors would not have taken such a heavy toll.

Would you say that in general, peacekeeping operations fail to prioritize these issues in their early days?

Absolutely it is a problem with peacekeeping itself. There isn’t any agreed framework for mutual accountability between the international community and the national actors, when a peacekeeping operation is established. We need to have something different instead of a status of mission agreement, something that goes well beyond the technical issues of freedom of movement and the inviolability of privileges and immunities. We must go far beyond that.

For all peacekeeping operations, the UN must create a framework of mutual accountability that would bind the recipient of international assistance to certain terms of behaviour and performance in return for all the generous assistance and help the international community is bringing in.

For all peacekeeping operations, the UN must create a framework of mutual accountability that would bind the recipient of international assistance to certain terms of behaviour and performance in return for all the generous assistance and help the international community is bringing in. It shouldn’t be a one-way highway. Mutual accountability must be central to peacekeeping. After all, peacekeeping operations are deployed with the consent of receiving Member States.

Could you go into a bit more detail about what you envision as the alternative?

I don’t like to call it conditions-based, because it means it would be an imposition. When I say ‘framework of mutual accountability,’ it means that there would be voluntary assumption of certain obligations on the part of both sides. We brought in that element, but very late in the context of this transition, in the peacebuilding plan that the Security Council asked of us last year. We developed it with the help of the Peacebuilding Commission.

Initially, I was pushing for a compact, but that sounds like a treaty. What do you do if the Government doesn’t fulfil its obligations? Do you take the Government to court? They dropped the idea of a compact, and I settled for something less, and now we call it a ‘framework of mutual accountability.’ That means that we agree on a set of priorities that are shared. You and I sit down and agree that these are the priorities on which the government should focus its energy and resources in the short-term, the mid-term and the long-term; and, this is how the UN and the donor community should support the agreed priorities, so the framework of mutual accountability sets obligations for both sides. We help, but then these are the things that you need to do so that we can help you. Quid pro quo!

Would this framework be best positioned in late-stage peacekeeping, especially considering that mutual accountability would be hard to implement in the situation of a failed state where missions may be deployed?

Absolutely no. As you build the institutions, as you help with the stability that leads to the emergence of a political leadership with a semblance of representative legitimacy, mutual accountability should be part of the process from the very start.

For instance, we haven’t waited for the winner of this election to be announced. We were already talking with the front-runners, and getting their commitment to certain critical processes that have not reached a point of maturation, including on the key issue of national reconciliation. We did this to make sure that the winning candidate remains steadfast in their commitments. We are hoping that the candidate who comes to power at the end of this exercise will remain committed to the vision of national reconciliation, to build for the first time a nation that’s united around a single vision, a shared idea that will carry Liberia into the future.

Speaking of hope, are you confident in the future of Liberia? Do you have hope for this country?

Let me put it this way. Hope in Liberia must be harboured by all of us. We cannot afford to be pessimists. Without hope, everything would have been in vain. I am hopeful because Liberia has come a long way since the end of the war. The many initiatives the Sirleaf Government has undertaken, with significant investment from the international community, have had a tremendous impact on bringing Liberia to where it is today. That should be reason enough for us to entertain the hope that this progress can be sustained.

Will it be? That depends on several factors. It depends on the degree of the political commitment of the new leaders to the reform agenda as well as the willingness of the international community to maintain a robust level of engagement so there won’t be a cliff, cutting off assistance soon after our departure. That’s why we’re lobbying for strengthening the UN system after UNMIL’s departure, so that part of our residual responsibilities will be taken over by the Country Team to fill part of the void that we will be leaving behind.

What we hope to leave in place when UNMIL closes is a strengthened set of coordination mechanisms for the UN system as well a strengthening of each of these UN agencies, funds and programmes together with some predictable, sustainable funding for them.

Are you confident the drawdown and completion of UNMIL and handover to the Country Team will be effective in continuing Liberia’s progress?

On the Government side, we completed transition of all security aspects as of June last year. And so far, so good. They are doing a good job. And if they can sustain it, that would be fantastic. However, the reform processes aren’t yet changing mindsets, aren’t yet improving the professional quality of the service personnel in the leeward areas. These are long-term processes that will take a generation to mature. But I hope that this progress will be sustained by the infusion of political commitment and resources.

On other things that are more policy-driven, we heavily depend on the commitment of the new leadership that will emerge as it goes on.

They must be committed to promoting the idea of a just society for maintaining peace. Without justice, there cannot be peace. To ensure that there is peace and stability in this country, Liberia must solidify its foundations of justice. And that’s not just through improvement of the judiciary, adjudicating crimes more quickly, and bringing accountability. Solidifying the foundations of justice also includes opening the political and economic space for the participation of all segments of society to share a future and share resources and opportunities.

"Solidifying the foundations of justice also includes opening the political and economic space for the participation of all segments of society to share a future and share resources and opportunities."

I’m not asking for everybody to immediately be given a chair at every school, or free medical insurance for all, or for everybody to have a job. But Liberia needs to begin a process that would gradually lead in that direction. This country is rich enough, with huge resources already available in nature, to start this process with the help of the international community. With so many kids not going to school, you are taking away the future of the country. We must look at both the quantity as well as the quality of education here. And that requires a long-term perspective, visualizing the ideal destination and building the steps toward achieving that objective in a way that one step could contribute toward the next step.

On a final note, what would you say to the people of Liberia and to the internationals working here to help the country move forward into the future?

First to the leadership of Liberia: The position you hold is given to you by the very people you will be leading. The first and most important thing to do is to recognize that this position is for serving the people. You cannot serve the people unless you know who the people are, what they want, and how you can provide them the services.

That’s how they can really, morally and ethically, claim legitimacy for their position in the Government. That’s the only way they can justify their salaries and enjoy the benefits of the job. If they don’t serve the public, then the social contract is off. They cannot enrich themselves with the wealth of the people and keep the people deprived of everything that belongs to them. So that is the message. Fight corruption. Make sure the Government efficiently delivers the services the Government is expected to deliver. Support all segments of society. Give people the space, the opportunity, through legal reform, through structural reform, through well thought-out policies to unleash their potential to the maximum.

Nature has given them so many riches: able-bodied men and women, fertile land, plenty of water and plenty of minerals, along with a diverse culture and a rich history. All those riches of the nation, put together, can make Liberia self-reliant and prosperous. But achieving these takes commitment, accountability and hard work, along with fighting corruption, nepotism and other unethical practices.

And to the international community helping Liberia move forward, what would you say?

Move away from the pet-project approach. Coordinate, so you will have a better bargaining position with the national authorities. Help them get a focus on the top priority areas in terms of diversification of the economy to produce and generate wealth, and delivery of services to the people.

Use your collective bargaining capacity to move things in the right direction for the benefit of Liberia. Since you have come here to assist another country, share the knowledge of how you plan your own economy back home, how you diversify and share your resources.

Human rights and gender issues – including having more women in Government positions, eliminating female genital mutilation, eradicating domestic violence – all these issues could be addressed effectively, but not without building a strong foundation on which Liberia can become self-reliant and become a contributor instead of a recipient of foreign assistance.

In the UN, we need to have a good understanding of an operating theatre before we craft the mandate. We must know why we were mandated to come into a country, why that country ended up in conflict in the first place. After identifying the core causes of the conflict, the main drivers of the crisis, the UN steps in and starts to help address those issues in a fundamental way. The structure of peacekeeping mandates should be focused on those priority areas. We must not continue to build the roof first. We must start with the foundations. We will eventually get to the roof, but first we must build the capacity that will contribute to self-reliance. Peacekeeping, peace consolidation and peacebuilding should not be seem as a continuum, but rather as integral parts of an indivisible peace process, with adequate predictable resources for promoting all aspects.

In addition to this, we must constantly look at ourselves and evaluate our own behaviour. The way we are perceived by the host population has a direct impact on the degree of our success in discharging our mandate. Are we all behaving ethically and morally in relations to our duties, and in our relations with local population, particularly women and children? Do we take seriously our responsibility towards our host environment, and are we respectful of the local laws and ethos? Simple things, such as unnecessary use of honks, sirens and lights or disrespect of traffic regulations can have a very damaging impact on the minds our hosts. The UN enjoys a lot of respect in this country. People appreciate us for the fact that we helped bring peace here. So, we should not squander this hard-earned respect by engaging in any unethical, immoral, disrespectful or irresponsible behaviour.

Another important issue is making good choices for mission leadership. Bureaucrats can never be leaders. Those who come to mission leadership with the intention of using the position as a stepping stone to another job should be given something somewhere that is not consequential.

People who are entrusted with the leadership of a mission that has so much impact on a nation – those people should be selected very deliberately according to proven leadership competence befitting the complexities of the tasks they will shoulder.

What’s needed are people with vision to bring about that kind of commitment to turn the minimal resources we have at our disposal into an instrument of change, and to be courageous enough to engage the authorities candidly instead of protecting themselves in order to avoid becoming a persona non-grata. We should remember that we come from an Organization whose charter specifically starts with ‘we the people….’ It doesn’t say ‘we the government….’

"It is the people in whose name we are deployed in the United Nations. We must remain true to that core principle. "

It is the people in whose name we are deployed in the United Nations. We must remain true to that core principle. We are the auxiliary forces of an Organization that has been established by the will of the people. Therefore, our loyalty should rest with the people of a nation where we are being deployed to serve. If we keep that in mind, then dealing with the authorities should become easier. We should serve and help those authorities who are representing and serving their nation. That’s why we’re here, working for the same cause.

Aerial view of the Pan African Plaza, UNMIL Headquarters in Monrovia. Photo: Albert G. Farran | UNMIL | 23 Jan 18

UN

UN United Nations Peacekeeping

United Nations Peacekeeping

![The story of UNMIL [Book]: The election of President George Weah The story of UNMIL [Book]: The election of President George Weah](https://unmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_image_thumb/public/field/image/george_manneh_weah_is_inaugurated_as_the_new_president.jpg?itok=FOVTGzEV)