Rule of law in multi-dimensional peacekeeping – lessons for reform | Melanne A. Civic, Principal Rule of Law Officer

The Principal Rule of Law Officer manages the justice, corrections and security sector reform components of the Mission, coordinates across UN police and human rights sectors, and collaborates with other Mission components, and with the UN Country Team and the international community with respect to rule of law in support of the Liberian Government. Melanne Civic is a former Senior Rule of Law Advisor with the United States Department of State, first with the Secretary of State’s Office of the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization, and then with the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations. She gave this interview in October 2017.

What is your background and experience, and how does it bear on the work you’ve done at UNMIL?

I came to UNMIL with nearly 20 years of experience with the US State Department, following several years with international civil society and nongovernmental organizations. For more than a decade, I coordinated closely with the UN and the international donor community on stability operations, specifically in rule of law and security sector reform related to conflict prevention and civilian-military cooperation. My rule of law and security experience was built on a foundation of diplomacy, international human rights and humanitarian law and policy, as well as expertise in international and transboundary environmental diplomacy (e.g., multi-country water sharing), and natural resources and conflict prevention.

I also was a leader in developing civilian and uniformed surge crisis response capabilities in international stability operations and conflict prevention.

I arrived at UNMIL in 2015 as the Mission was taking critical steps to integrate its justice and security activities. In 2012, UNMIL had started the process of reconfiguring its approach to rule of law to achieve greater coherence of support to the Liberian Government. As Principal Rule of Law Officer, I was mandated to coordinate across the justice-security continuum, bringing strategic and operational experience, technical expertise, and a commitment to advance coordination and collaboration.

I undertook the final stage of integration across the justice-security continuum by restructuring the justice, corrections and security sector reform components of the Mission under a single service, the Rule of Law and Security Institutions Support Service. The vision of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General was to achieve not only coordination across the justice and security sectors, but also cross-cutting rule of law support capacity, such that justice, corrections and security sector reform technical experts and advisors worked cooperatively. This approach had been particularly needed to achieve greater efficiencies with Mission downsizing and impending closure. This experiment in integrated support to the Liberian justice, corrections and security institutions lasted nine months, and demonstrated its value in providing a mutually supportive model which also encouraged coordination among the Liberian ministries.

What challenges did you face when seeking to coordinate and ultimately integrate?

When I arrived, I found considerable inertia to making these changes, particularly from within the Mission. Coordination in the abstract is widely extolled. Yet individuals and organizations tend to resist or reject actually being coordinated. Integration has been seen as relinquishing a measure of control, autonomy, authority…and glory. No longer would a specific manager or component head be said to be the singular force behind a given achievement or outcome which was accomplished through teamwork. My task was not only to break down sectoral and subject matter barriers, but also to be mindful of egos and the territorial barriers to coordination and collaboration across the justice-security continuum.

It was a learning process in various UN missions, including at UNMIL which necessitated me taking distinct nuanced approaches.

Knowing this, I emphasized complementarity – advancing opportunities for cooperation across rule of law within UNMIL, with the UNCT, and with international partners. With the international donor community, I actively strengthened information exchange in strategic planning, and met with bilateral and multilateral partners to identify specific areas for cooperation through our complementary assets.

What did you hope to achieve and what lessons have you concluded are the distinct comparative advantages of UN peacekeeping?

I sought not only greater efficiencies, but also to capitalize on comparative advantages. Drawing from my previous experience in the donor community, and these three years at UNMIL, I am of the view that the most consequential comparative advantage of UN peacekeeping missions is not just good offices in the context of the politically neutral arbiter, but the UN’s convening authority given its political neutrality and gravitas.

I am of the view that the most consequential comparative advantage of UN peacekeeping missions is not just good offices in the context of the politically neutral arbiter, but the UN’s convening authority given its political neutrality and gravitas.

This role as the neutral convener is essential because missions can facilitate enhanced information sharing and coordination among host nation leadership and its citizenry, and among and between international partners, enabling efficiency and synergies.

I also discerned that the UN enjoys a comparative advantage when working directly with and strengthening civil society, even more than donor countries have, whose focus is predominantly on government-to-government relationships. This was apparent, for example, with respect to supporting the Government in addressing the challenge of prolonged pre-trial detention, which is identified as a driver of conflict. I emphasized support to public defenders, in particular through international civil society organizations best placed to strengthen local civil society and to catalyse public pressure to strengthen public defence. I briefed donor partners who were focusing their programmatic support on the prosecutors and law enforcement elements of the criminal justice chain.

Is it fair to say that rule of law both affects all other peacekeeping and peace building activities, and similarly is affected by such activities?

Yes and no. Rule of law is one lens for peacekeeping. With good argument, human rights could say this as well, as could political affairs, good governance, and security sector reform. If it can be argued that any one sector has the most far reaching, cross-cutting impact, it is human rights support. Without the integration of human rights in rule of law, for example, the result could be despotism – rule by law, as justice and security sectors would advance the power of those governing without protecting the rights and needs of the people.

The components of multi-dimensional peacekeeping missions operate best as an interconnected whole, visualized as a Venn diagram of interrelationships, without the necessity of determining pre-eminence for any one sector, yet with a critical cross-cutting role for human rights.

Why is rule of law important in peacekeeping and in Liberia?

Rule of law is a foundation for nonviolent dispute resolution, and a mechanism to improve transparency, accountability, and justice through the equal and universal application and enforcement of the law. As such, rule of law promotes sustainable peace and stability.

With the establishment of the modern Liberian state, the country has enjoyed a governance and legal structure that provides democratic justice and institutions, as well as a vast body of legislation that forms the backbone for the rule of law. Yet challenges of enforcement of the laws, justice under the law, equal application of the law, and transparency remain, as do divisions between indigenous peoples and those of African-American descent. Persistent entrenched corruption is the preeminent threat to stability, safety and security in Liberia.

What would you say are some of the Mission’s most notable achievements in the 14 years it has operated in Liberia?

From my perspective in rule of law, UNMIL’s most notable achievement is the building of trust among the public, and between the people of Liberia and the security institutions, and in particular improvements in trust in the police and the de-politicization of security institutions. With the total breakdown of law and order, well more than a decade of civil war, and the politicization of security institutions, trust had been fundamentally destroyed. UNMIL became not only a provider of security, but a symbol of safety and stability for the people of Liberia and the foundation for demanding it of Liberian institutions. Further, UNMIL good offices advocated for transition back to good governance.

Are there other incremental or “silent” improvements in rule of law that might not have made headlines but which have made an impact for sustainable peace in Liberia?

UNMIL’s most notable achievement is the building of trust among the public, and between the people of Liberia and the security institutions, and in particular improvements in trust in the police and de-politicization of security institutions.

Among the “silent achievements” I would include the enhanced representation and role of women in Liberian security institutions, including in the corrections sector, the armed forces, the police and others. This is a Liberian achievement, largely driven by women breaking through the norms of a patriarchal society, which was advanced through UNMIL’s advocacy, facilitation and financial programmatic support.

Liberia has played an auspicious role in advancing gender mainstreaming, having elected the first woman president in Africa. Women now participate professionally across Liberia’s security institutions, and, also, with UNMIL support, gender offices have been established within all security institutions.

When I speak with individuals and groups of women across Liberia’s security institutions, I see great pride and courage as they have entered predominantly male institutions and made an impact on policy and operations.

Another “silent achievement” has been advances specifically in corrections, which have been significant with support by uniformed corrections officers who were contributed by Member States, and civilian UN corrections advisors. In particular, advances in professionalizing prison management personnel, and building capacity in prison intelligence and investigatory skills enable prison officers to interpret early warning signs and to respond to security threats without escalating violence. The training of female corrections officers alongside male counterparts has significantly advanced gender mainstreaming.

UNMIL provided multi-faceted support to gender mainstreaming in Liberia’s security institutions by facilitating the establishment of gender units training for gender coordinators, and providing a platform for discussion on challenges faced by women in this predominantly male sector.

Also highly impactful was UNMIL’s support to improving transparency and accountability of the criminal justice system by introducing data management capacity for the prosecutorial, judicial, and corrections institutions—that is the ability to systematically track each stage of a criminal case, from arrest to detention, indictment, trial and sentencing. As recently as 2016, prison inmate records were kept on chalk boards, allowing pre-trial detainees to slip through the cracks. Poor data management highlighted weaknesses in the system, including excessive delays in processing cases. I strengthened the adversarial system of justice under the common law model, engaging donors and international civil society organizations through coordinated capacity building and mentoring support.

On the issue of corruption, how have you dealt with it here in your work and what’s your view about the way forward?

I would put corruption as the most significant and impactful area of unfinished business as UNMIL looks towards its drawdown and closure. Resolving entrenched corruption will need to be tackled to ensure the sustainability of reforms. Whether UNMIL was best placed to address corruption or not is another question entirely. Let me cite policy analyst Sarah Chayes. She identifies corruption as basically a virus that will spread and undermine all types of efforts for sustainable peace, and I would be in that school of thought as well.

UNMIL and the international community supported the establishment of the Liberian Anti-Corruption Commission, yet it has been considered to have no “teeth,” with a severely limited role in investigation and prosecution of high profile cases. It has operated under a cloud of corruption from within, as well.

International donors have the capacity to hold recipients of foreign aid accountable, and potentially to cut the purse-strings. However, this is not often done by the donors, for a myriad of strategic, diplomatic, and national security reasons.

The international donor community has greater leverage to address corruption than the UN, in the sense that the levers of foreign aid and grants create opportunities for enforceable agreements through which corruption can be concretely addressed. I say enforceable because while the UN does make efforts to establish compacts, frameworks for mutual agreement and mutual responsibilities with the weight of Member State backing, the UN does not have enforcement authority, and relies on political persuasion and good offices interventions. International donors have the capacity to hold recipients of foreign aid accountable, and potentially to cut the purse-strings. However, this is not often done by the donors, for a myriad of strategic, diplomatic, and national security reasons.

Many countries that struggle with stability and are re-emerging from conflict do not have freedom of speech or strong civil society organizations.

Yet Liberia does--in particular a bold and vocal press--and this is very much in its favour. Unfortunately, domestic civil society in Liberia tends not to work cooperatively, and this undermines its ability to coalesce support for positive change. The press and civil society in Liberia exert only a limited “watchdog” function. These institutions have genuine potential to hold public officials accountable, and catalyse and organize change movements. I would suggest instituting enhanced mentoring relationships and cooperative engagements between international and Liberian domestic civil society.

What would you say are the main challenges this Mission has faced, and perhaps continues to face as it comes to a close?

The most consequential challenge I have observed is identifying and cultivating national will.

The most consequential challenge I have observed is identifying and cultivating national will. It is a well-established tenet for foreign aid and support that national ownership – the active interest and role of national stakeholders in setting priorities in making decisions, and executing programmes supported by foreign aid – is critical to achieve culturally appropriate change and sustainability. In other words, the host country must determine its priorities, have the will to change and to build capacity and to drive the change. I’ve seen examples in other countries where national will is not cultivated, where the high degree of inefficiencies or diffuse national will frustrates the timelines for foreign aid and programme implementation. In those cases, the donor might impose external will, which may not be contextually or culturally appropriate. In extreme instances, a battle of wills may ensue such changes that, most likely, will not be embraced or sustained by the host country. Yet, what should the UN and donor community do where there is such limited political will to cultivate, where complacency appears to prevail, and where elites predominantly prioritize personal gain at the expense of the public good, national stabilization, and development?

When I came to Liberia, I carried with me the lesson that national ownership is critical for the sustainability of reforms. Yet I found an exceptionally low level of political will, so I provided to UN Headquarters options for enforceable compacts. I proposed that strong Member State support should be sought to generate incentives and cultivate national ownership by holding the Government accountable to its commitments with respect to foreign assistance.

|

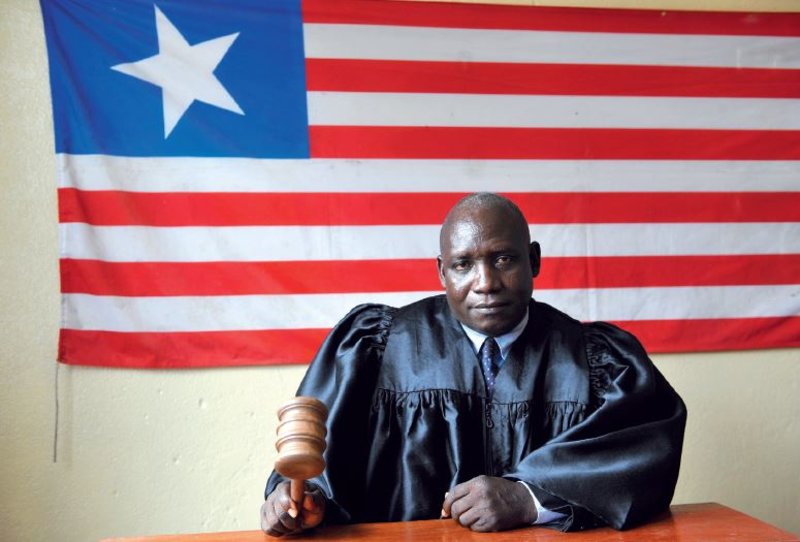

| A Liberian judge sits in front of the Liberian flag at the Court of Justice in Careysburg, Montserrado County. Photo: Staton Winter | UNMIL | 12 May 11 |

What lessons would you recommend for the multi-dimensional peacekeeping model? Is there anything that UNMIL could have done differently to achieve greater impact?

Based on my experience in this peacekeeping Mission, from my previous donor perspective, and my experience coordinating with other UN peacekeeping missions when I was with the US Government, I would propose that technical and capacity-building support to rule of law--and to other sectors as appropriate-- need not and should not be placed within the peacekeeping mission itself.

I propose instead taking a modified approach to multidimensionality, of complementarity with UN Agencies, Funds and Programmes and donor development organizations from the get-go as soon as the security environment permits. I propose further that clearer distinctions be drawn between peacekeeping versus transitional, medium and longer-term development support. When I came to UNMIL and saw the full array of rule of law outputs planned for the fiscal year, it read to me largely like a transitional and medium-term development programme. It is clear that development need not and should not be performed by peacekeepers.

A peacekeeping mission should focus on good offices, advocacy, and its convening authority, where it would have the greatest comparative advantages.

A peacekeeping mission should focus on good offices, advocacy, and its convening authority, where it would have the greatest comparative advantages. The mission essentially would be the hub, as the source for good offices and political leadership, with a small cadre of sectoral experts coordinating across the UN Country Team and the international community. The technical sector expertise and capacity-building programmes would be provided by the UN Country Team and bilateral and multilateral partners and development organizations, rather than directly by the mission. The multidimensional approach thereby would manifest as a coordination capacity, convening the UNCT and donor community, while retaining a relatively small cadre of sectoral policy experts who are familiar with technical issues and who facilitate consensus and coordination.

What recommendations would you have for Liberians themselves moving forward?

Liberia’s peaceful transition of power with the 2017 elections, despite political and procedural disputes, has demonstrated its resilience, stability, and rule of law culture.

Liberia’s peaceful transition of power with the 2017 elections, despite political and procedural disputes, has demonstrated its resilience, stability, and rule of law culture. Even where alleged voting irregularities and disputes arose during the electoral process, they were resolved through the courts, and with protests and petitions, peacefully, not resorting to violence. The Supreme Court decision was respected and acted upon without a backlash of violence erupting. These are highly significant achievements and bode well for the future of Liberia.

Additionally, I have seen signs of hope at the mid-level of the Liberian Government: I see a new generation of civil servants infused with ideals of professional integrity. But the caution is, will some be corrupted before they become the future leaders? Is the status quo stronger than the forces of change? Support from the international community, for human rights monitoring organizations and sustained anti-corruption programmes will be pivotal.

I see a new generation of civil servants infused with ideals of professional integrity. But the caution is, will some be corrupted before they become the future leaders? Is the status quo stronger than the forces of change?

So what recommendations would you give to the internationals who are going to continue work here helping Liberia move to the future?

First, I recommend greater concerted efforts at preventing corruption, which the international community is well-placed to do. Second, I recommend focusing on civil society, which resides with international development.

Priorities moving forward include providing capacity-building support for budgeting, resource and financial allocations, within strong anticorruption programmes as donors are pursuing. Beyond rule of law and human rights, I recommend continued support by the international community in assisting Liberia to responsibly develop its natural resources base, in particular agriculture and animal husbandry, and associated market distribution networks and infrastructure development. Liberia has vast arable land, yet the prevailing culture does not favour local products or local agriculture.

On the Secretary General’s goal of 50-50 gender parity among UN staff, do you have any observations about UNMIL’s record and lessons for other missions?

Considerable thought at UN Headquarters has gone into the question of achieving 50-50 gender parity, and there is a growing recognition that this will require not only enhanced recruitment efforts, but also a vision for the retention of women at mid-level and senior leadership.

At UNMIL, under the leadership of an SRSG who highly valued the contributions of women, I observed a marked reduction of women in Mission leadership. When I started, half of the director positions were filled by women, as were five of 13 or 38.5 per cent of senior leadership posts overall. During fiscal year 2017-18, only one out of six director posts was held by a woman, and only one member of the senior leadership was female, a reduction to approximately 9 per cent. It would be informative for UN Headquarters to collect data on the retention of women in management and leadership positions, particularly through changing events such as structural reorganizations and downsizing.

The inherently limited term of a peacekeeping mission creates specific challenges for recruitment and retention of UN women and men.

The process paradoxically tends to engender an extreme individualism on the one hand, and manipulation of the hiring system by some in management on the other hand. Staff struggle to keep their positions while facing multiple reorganizations and post cuts in downsizing, some which appear anecdotally to disproportionately impact women. I have seen this phenomenon undermine not only the assets of diversity, but also teamwork, morale, and ultimately productivity, outputs and impact.

A greater emphasis on secondments and government-provided personnel, so that staff have an assured job to return to following mission work, would help address some of the negative impacts of the tenuous nature of a peacekeeping career. It would also combat complacency and the manipulation of existing rules and policy.

|

| Silhouette of a detained soldier in Liberia. Photo: Staton Winter | UNMIL | 25 Jan 13 |

UN

UN United Nations Peacekeeping

United Nations Peacekeeping

![The story of UNMIL [Book]: Independent National Human Rights Commission gets recognition The story of UNMIL [Book]: Independent National Human Rights Commission gets recognition](https://unmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_image_thumb/public/field/image/female_students_marching_on_the_streets_of_monrovia_to.jpg?itok=4qK9pFr6)

![The story of UNMIL [Book]: UNMIL and the National Elections Commission The story of UNMIL [Book]: UNMIL and the National Elections Commission](https://unmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_image_thumb/public/field/image/official_certification_ceremony_of_the_winners_of_the.jpg?itok=PdrGXJdR)